Many commercial synthesis providers use software tools to flag sequences of concern (SOCs) that could facilitate the construction of dangerous biological agents. To decide whether to fulfil flagged orders, providers conduct customer screening (also called KYC; Know-Your-Customer or Know-Your-Collaborator) in an attempt to answer the question: is the customer conducting legitimate life sciences work?

Customer screening has been a priority for IBBIS since work began on the Common Mechanism in 2020, and IBBIS released our first set of resources for customer screening in June 2025 to support:

- Onboarding new nucleic acid synthesis customers using the New Customer Form and decision guide

- Handling orders for sequences of concern using the SOC Order Form and decision guide

- Training customer service representatives using an order screening game, which IBBIS offers as a workshop or a set of materials (slides, customer profiles)

As we developed these tools, we wanted to ensure we remained aligned with national and international guidance on best practices for customer screening. We recently shared a new preprint, Implementing Emerging Customer Screening Standards for Nucleic Acid Synthesis, that describes our experience attempting to translate the emerging consensus on appropriate KYC practices into practical tools.

An emerging consensus

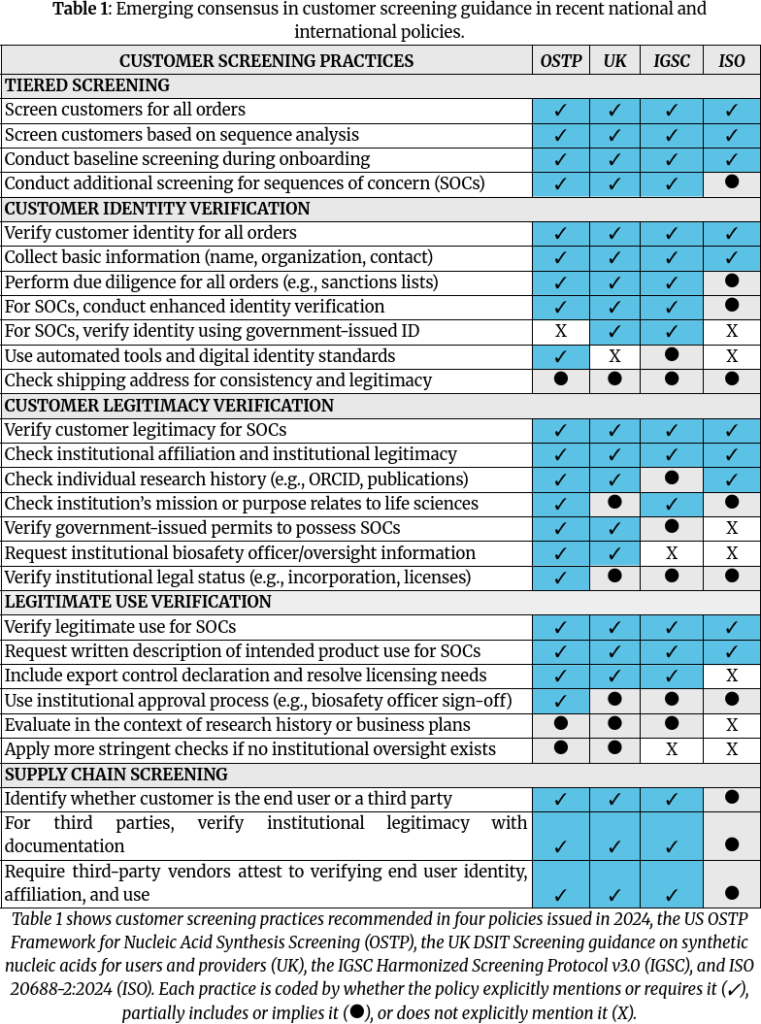

The paper first outlines five core practices for customer screening that emerged in both international and national-level guidance in 2024:

- Tiered screening for all orders, with additional screening for orders that include SOCs.

- Customer identity verification for all customers.

- Customer legitimacy verification for customers who order SOCs.

- Legitimate use verification for orders that include SOCs.

- Supply chain screening to address third-party vendors and multi-party distribution.

Specific practices are shown in Table 1 of the paper, which is reproduced below.

Implementation challenges

Our experience developing the customer screening forms showed that significant work was needed to translate the consensus practices into practical tools. There are persistent ambiguities around appropriate due diligence and decision-making when implementing these practices, especially in a fragmented global context. A few of the challenges we encountered were:

- Two tiers may not be enough. The two tiers in current guidance (“all orders” and “orders containing SOCs”) may not be sufficient to reflect the risk from synthesis orders, especially given that some sequences fall under additional regulatory control, such as the UK SAPO or US FSAP licensing programs. The paper’s Appendix includes a five-tier rubric of screening practices.

- Legitimacy indicators vary globally. Some well-established, highly-reputable research labs (including some funded by the Institut Pasteur and CEPI) lack formal institutional approval processes like biosafety committees. In some parts of the world, legitimate researchers often use personal email addresses even when affiliated with established universities.

- Flexible forms may not elicit enough information. Written descriptions of intended use can be difficult to interpret, and customers are often unwilling to provide sufficient detail. Providers report that, when asked to provide an intended use, customers frequently write “research purposes” with no further elaboration.

Looking ahead

The preprint concludes with five recommendations to strengthen customer screening:

- Establish minimal globally-relevant baseline for customer screening. Similar to recent work defining a baseline set of sequences of concern, it should be possible to define customer attributes that all providers agree should merit additional screening, such as attempts to remain anonymous, requests to ship to residential addresses, or names matching the UN sanctions list.

- Clarify customer screening through practical case studies. Additional case studies, especially those describing indicators of institutional legitimacy with broad geographical and sectoral representation, and real-world examples of third-party vendors that challenge supply chain screening.

- Encourage automated identity verification with clear guidance. This includes best practices for using existing software for identity verification and sanctions screening, exploring transferable identity verification linked to identifiers like ORCID, and developing best practices for verifying the legal status of smaller or newer life sciences institutions.

- Leverage existing approvals to demonstrate customer legitimacy. Rather than each provider independently assessing legitimacy, screening systems should build on existing institutional oversight and government approvals. Pilot projects like SecureDNA’s Exemption Certification System and Cliver’s AI-powered researcher history summaries point toward possible approaches.

- Integrate sequence and customer screening. Tiered customer screening should include appropriate due diligence at additional tiers beyond “all orders” and “orders including SOCs.” This will require standardizing sequence screening outputs to reflect shared risk tiers and cross-referencing identity verification guidelines (like NIST SP 800-63) to orders at different biosecurity risk levels

In early 2026, IBBIS plans to undertake a landscape analysis to determine which of these recommendations to tackle as part of our customer screening workstream. If you are working on customer screening, managed access, digital identity, or other relevant topics, we would appreciate your opinion. Please get in touch with tessa@ibbis.bio.